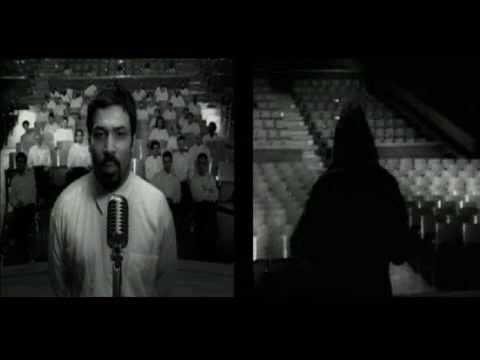

Shirin Neshat’s Turbulent (1998) opens with two black-and-white images of the same auditorium. The images appear and fade almost immediately. One shot features a group of men dressed in white shirts and black pants as they sit quietly in anticipation. The other shot shows an empty auditorium.

Then the two filmic images reappear. (Turbulent is a video installation designed to project both films simultaneously on opposing walls of the same room.)

On one side, we watch a charismatic male performer—Iranian artist Shoja Azari—take the stage and begin singing into an old-fashioned microphone. Azari is lip-synching Iranian singer Shahram Nazeri’s rendition of a 13th-century Rumi poem which has been set to music. Strangely, Azari faces us, not his audience. So we are seeing Azari with the group of men pictured behind him. One is reminded of political rallies, with supporters on bleachers waving signs and clapping as they sit behind a candidate.

Azari finishes singing, and the all-male audience bursts into applause. Azari has lost himself so utterly in the performance that the sound of the applause seems almost to momentarily startle him. As Azari bows, he is suddenly interrupted by another sound, from the opposing screen. We begin to hear the mangled, unintelligible sounds of a female performer as she begins singing to an empty stage.

This is not music with distinct time signatures and appropriate, measured expressions of passion. These sounds—sung by Sussan Deyhim—are primeval and at times multi-tonal. She’s ululating, screeching, grunting. These sounds hearken to the ocean, to animals issuing calls in the jungle, to childbirth. It’s as if she is expressing a pain that is too horrible to ever be defined by words. These noises seem to emanate from the very depths of her being.

Not only is her performance about twice as long as Azari’s, but the camera also treats her differently. It circles around Deyhim during her performance, whereas we only get one static, frontal shot of Azari.

One feels as if Deyhim is singing about a pain particular to the female experience. It sounds like a mournful response to being ignored, and yet she has caught the attention of the man on the opposing screen. He watches, silently taken aback, until she finishes singing. The performance is a release, and then she goes silent.

Arguably the most famous Iranian-American artist working today, Shirin Neshat is known for dealing in binaries and “dual screens” of all kinds. This is true especially of the period of her career when she made Turbulent.

In an interview with Scott MacDonald, Shirin Neshat explains that the operating mechanism in Turbulent “was the notion of opposites: the man, the woman; black, white; empty auditorium, full auditorium; traditional music, totally improvised music; a conformist versus a rebel.”

Citing film history, Neshat’s interviewer wonders if the circular motions around Turbulent’s female singer are meant to suggest womanhood, in contrast to more “phallic” filming techniques that indicate male-ness. Neshat says that the circular camerawork around the female singer is actually intended to convey the woman’s emotions—specifically “her mental state, her madness, her rage.”

Neshat also says of the two singers, “Having clearly proved herself through her unbelievable performance, she appears relieved and peaceful whereas he comes across as shocked and at a loss.”

It’s Neshat’s piece, so usually I’d leave it there. I think though that part of what makes Shirin Neshat so successful—so global—as an artist is that while she’s speaking in very particular terms, her work often touches upon a certain universality in its visual and auditory language. The lack of translation offered in her work almost enhances its ability to communicate in multiple languages. In the space between all those black-and-white contrasts, ample room for interpretation emerges.

I was thinking about Shirin Neshat a lot when Donald Trump won his first Presidential election in 2016. Watching Hillary Clinton—a super-smart female technocrat with the right background but none of Trump’s panache—lose to him felt like a devastating reminder of all the gender-related injustice in the world. Neshat’s binaries—black and white, man and woman, applause and emptiness—really spoke to me. I vividly remember the cold, rainy day after the election and the disbelief on everyone’s faces, including my own.

I am, I guess, an old-fashioned liberal. I and others like me believe in institutions—that many old, imperfect things should stay in place but be refined and improved from the inside. Donald Trump enjoys breaking things, and his anti-establishmentarian tendencies seem to enhance his popularity. Of course he took down grown-up Student Council Kid Hillary Rodham Clinton.

The Rumi poem that we hear in Turbulent is all about the agony of being in love. I found what is an undoubtedly imperfect translation from the Farsi original. Here goes: “An excuse is enough to love you/A song is enough for the ones that are crazy for you/Why are you hitting with the blade of cruelty to kill me.”

While Hillary Clinton won the popular vote in 2016 by three million votes, this time Trump defeated Kamala Harris via both the electoral college and the popular vote. Trump won with a mandate.

Indeed, why are you hitting with the blade of cruelty to kill me.

I do notice that this time around I feel less glum. No liberal podcast host can convince me that Harris ran a great campaign. Outside her strong debate performance Harris was frequently unable to answer a variety of important policy-related and political questions in a clear way. Harris appears to have avoided significant media and interview opportunities that could have expanded her voter base.

Binaries are an important starting point and they make for compelling, eye-popping art, but nobody ever fits entirely into any of them. Kamala Harris is a great example of that. She is a beautiful woman, and she is a former prosecutor. She has long, feminine nails and a manicured appearance, yet she is a gun owner who would have no compunction about shooting an intruder. In her long career she has acted both super-tough and super-liberal. And on and on.

Donald Trump actually seems significantly more locked in by the constraints of gender than Harris does. It would, I think, take quite a bit of work to sustain that super-tough, alpha-male posture all of the time. I don’t get the sense that Trump has a strong sense of self or a stable core identity. A lot of individuals and interest groups with neither a liking nor a respect for Trump stand to profit from his second term, and they surround him. That too must carry a weight.

In the same interview mentioned above, Shirin Neshat discusses her film adaptation of Women Without Men, a book by Iranian author Shahrnush Parsipur. The story centers upon five women who attempt to build a utopia for themselves in a bucolic Iranian house. Neshat comments, “What is interesting is how eventually this community falls apart. The utopia proves impossible due to the likelihood that every woman herself contains the flaws that she is running away from in the outside world.”

It would be naïve to think that gender is not a limiting factor in the context of a Presidential race. Emotionally I often live in the world I desire to make real, rather than in my actual flesh-and-bones one. I want to ignore the hindrances placed on all women in the same way I want to ignore the primal female singing—which is all too familiar and painful—in Turbulent.

Yet I do feel a change in the air, in the culture. The concept of a female President seems much less surprising to people now. Putting gender aside for a moment, next time the Democrats need to simply pick a winner, period.

Shirin Neshat observes to her interviewer, “Religion and poetry don’t play a big role in American culture.” Americans may not conceive of religion or poetry in the same ways as other people do, but I think we absolutely revere those things here, just in different forms.

Shirin Neshat has made important contributions to the way we understand Iran. See more of her path-breaking work here.

Are you depressed about the Presidential election, or anything else for that matter? Maybe we could all use a little more Rumi in our lives. Shahram Nazeri, whose agile, stately voice animates so much of Turbulent, sings more of Rumi’s poetry here:

My clients Dvir and Shalhevet Cahana hosted a deeply inspiring retreat in Miami the weekend of October 25th to honor victims and survivors of the October 7th terrorist attacks in southern Israel last year. They welcomed DJ Artifex, who survived that day and who was performing at the NOVA Festival when the event turned deadly.

Last year, DJ Artifex’s set was interrupted at 6:29 am Israel time. This year, DJ Artifex played his full set—from start to finish—for retreat participants at the Maze Lounge in Miami. He also shared his harrowing, surreal testimony from October 7th and told us a little bit about the many friends he lost forever.

Follow the Cahanas on Instagram as they continue to build their growing Jewish community in Miami.

See me in the DJ booth with DJ Artifex on my Instagram!